Osteoporosis is a loss of bone mass, where your bones become less dense. Rather like a bird’s bones compared to a mammal’s, the bones become lighter but also weaker: meaning they’re more prone to breaks and fractures. Osteoporosis typically affects older people and is a degenerative disease, meaning the symptoms worsen with the passage of time, but it can affect someone of any age and the onset of symptoms is unique to each sufferer.

Both genetics and lifestyles can alter the risk and severity of osteoporosis. This article explores the disease’s symptoms, and how sufferers’ lives can be improved through lifestyle changes, supplements and other treatments.

Contents

What is osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is a condition that weakens bone strength. The word osteoporosis originates from Greek, meaning “porous bones”. Our bones are made of a combination of tough yet elastic fibres (collagen) and minerals (mainly calcium and phosphorous). The latter gives our bones compressive strength, meaning they’ll stand up to our own mass and what we’re able to lift! Collagen provides our bones tensile strength, meaning they’re able to hold their own when being stretched, a little like steel cables in a suspension bridge.

Unlike our hair, our bones are living tissue. They’re comprised of cells that create, shape and maintain the strength of our bones. When we’re younger, our bone cells create more bone material as we grow. As we get older, from our mid-thirties and forties, our bones naturally start to lose some of their mass and become weaker.

Osteoporosis is a term used to describe people who suffer comparatively more severe bone loss, meaning they’re getting older faster. Their bones are older than their years.

How is Osteoporosis identified?

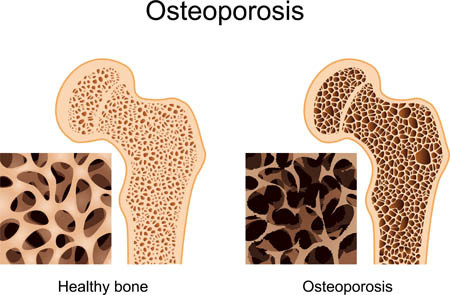

If you look at bone under a microscope, you will see that parts of it look like a honeycomb; our bones naturally have tiny porous holes. Osteoporosis sufferers have much larger holes in their honeycomb, explaining why the bones are less dense and their structure is weaker. Obviously, you can’t thrust your bone under a microscope yourself!

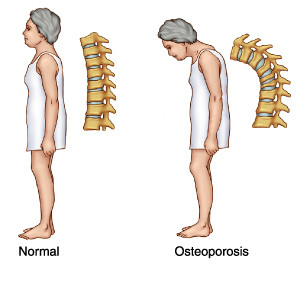

The typical signs of osteoporosis include experiencing breaks or fractures to bones after minor bumps and falls but also include shrinking in size, stooped posture (or hunched back) and persistent back pain.

The procedure for being certain you have osteoporosis is to have a bone density test. This test uses a small amount of x-ray to measure the amount of mineral in one or a small number of bones (often those in your lower back, hip or forearm). Doctors will often recommend bone density tests for people prone to fractures and breaks, or people who experience a fracture or break from a minor knock.

How common is Osteoporosis?

It’s very common, especially in older people. The National Osteoporosis Association estimate 54 million Americans are at severe risk or already have the condition. Approximately half of women and a quarter of men will break a bone in their lifetime due to osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis affects women more than it affects men, due to them naturally losing bone mass at a faster rate. This is partly due to the role of the hormone oestrogen in protecting bone density. After the menopause oestrogen levels fall, helping explain why the likelihood of osteoporosis increases from 2% in 50 year old women rises to 25% in eighty year olds.

What are the risk factors of osteoporosis

We’ve already mentioned the primary signs of regular bone breaks or fractures, or a minor knock leading to severe injury. Risk factors that help predict whether you may suffer osteoporosis include:

- Having a family history of osteoporosis.

- Being a smoker or heavy drinker (more than four units a day).

- Rarely or never exercising, instead leading a lazy sedentary lifestyle.

- Being severely underweight or anorexic (a BMI of 19 or less); not only does this mean you’re not getting the nutrition you need to maintain your bones, but it also reduces levels of hormones such as oestrogen that protect us against bone mass loss.

- Are or have taken steroids for more than three months.

- Lacking sufficient levels of calcium of vitamin D (often through poor diet and minimal exposure to sunlight).

Some signs and risk-factors specifically affect women:

- Having gone through the menopause at a young age (before 45)

- Just before entering the menopause, periods stop for more than six months

Certain medical conditions also increase the risk of developing osteoporosis including artheritis, chronic liver disease or kidney failure, Coeliac and Crohn’s disease, Cushing’s syndrome, diabetes (type 1) and other conditions that limit mobility.

Lifestyle changes to prevent and slow down Osteoporosis

We’ve already mentioned how smoking and drinking increases the chances of severity. Whether or not you’re suffering osteoporosis, quitting smoking and reducing alcohol consumption to safer levels (no more than 3-4 units a day).

Exercise can help to prevent osteoporosis, as it strengthens your bones and stimulates their growth capabilities. Exercises that bear your weight against yourself, such as brisk walking and running are particularly good as they don’t overstrain your muscles. For older people, a regular walk is a good start. However, the more vigorous the exercise, the better. You should aim to exercise for thirty minutes five times a week.

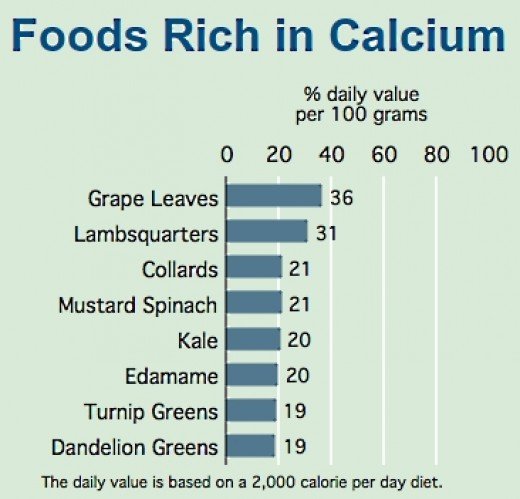

Diet is also of vital importance. Your body needs vitamin D in order to absorb the calcium, which in turn your body converts to bone. Like all the cells in your body, protein is needed to repair and create new cells. You should be consuming 600-800 IU of vitamin D possible through daily exposure to sunlight) and 0.8-1.3 grams of calcium (getting higher with age). 1 gram of calcium is achievable from litre of milk or 250g of yogurt.

Calcium rich foods aren’t limited to dairy products. In fact butter, cream and soft cheeses contain little calcium. Vegetables including curly kale, okra, spinach, and watercress are also good sources of calcium, as is bread and calcium-fortified soya milk. You can also increase your intake of Vitamin D by eating oily fish, having the added benefit of Omega-3 to improve your cognitive abilities.

Vitamin D and Calcium Supplements

As we get older, the risks of osteoporosis increase and our exposure to sunlight often decreases as we live a more sedately lifestyle, and our bodies become less adept at absorbing the vitamins and minerals we need. It’s for this reason many people in their late 50s and 60s start taking Vitamin D supplements. However, if you’re young and live a healthy lifestyle, you should not need to take Vitamin D supplements.

Similarly, you should only consider calcium supplements if you’re diet is naturally low in calcium. Try keeping a food diary and counting how much calcium is contained in the food you eat, boosting it if needed with the calcium-rich foods we mentioned above. Supplements should be a last resort.

Medication to treat osteoporosis

The medical treatments for osteoporosis should only be taken on the advice of your doctor. Never self-medicate, as you should balance the need for stronger bones with the risks associated with each of the following medicines. Your doctor will also likely recommend regular bone density scans, to test how successful different treatments are.

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) previously was one of the most common treatments used to prevent osteoporosis. However, in recent years scientific research has identified the potential long-term health risks of HRT (small increased risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular diseases) if it is used in the long term. It’s therefore now used if other simple medical treatments have failed.

Bisphosphonates are the most common treatments. They target bone-making cells and help to restore and prevent further bone loss. Alendronate is the most common of these drugs, with risedronate or etidronate used if people are intolerant to alendronate or it has limited effects.

For women who are intolerant to bisphosphonates, raloxifene can be used to mimic the effects of oestrogen. Over time, this reverses the excessive breakdown of bone and makes bones stronger.

Parathyroid hormone peptide drugs, such as teriparatide, and strontium ranelate can be used as a last resort if other drugs have failed. These have higher risks and severe side-effects, hence are left as a last line of defence.